Alright, if you've been following along so far, hopefully you have a good grasp on reducers. Say it with me:

Reducers take two inputs and return a single output

We've looked at reducers in exclusion, as well as how they can be transformed using transducers. Today, we're going to look at a slightly different type of reducer - ninja reducers! Yes, I did just make that term up on the spot, but I think you get the implication - these reducers are hiding in plain sight. They may not look like a reducer at first glance, but they are, I promise.

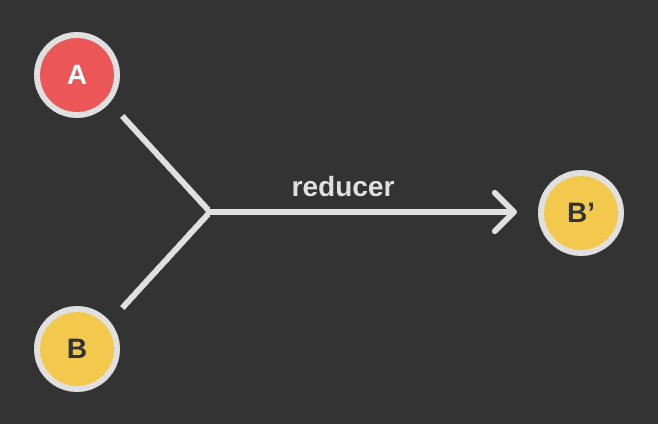

First, a brief refresher. When I say reducer, you should picture something like this:

An initial data source B is combined with some sort of modifier A and the result is a transformed

into a new data source B' (pronounced B prime). In practice, this flow takes many different names

and roles, but you should always be able to outline it in this Y-shaped, 2 becomes 1 pattern.

React Component State

Let's take a detour into frontend land and head over to the React corner. In case you're unfamiliar, React is (in their own words) "[a] JavaScript library for building user interfaces". It's beyond the scope of this article to go in-depth into React's state model and component implementation, so if you've never worked with a stateful component-based UI framework like React, take some time and head over to React's tutorial before reading any further.

Component classes should always extend React.Component and get access to setState as a result.

Component state lives in an immutable class instance variable named state. Since it's immutable,

it can only be updated using the setter method setState. Here's an example for some context:

import React from 'react';

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

state = {

clicked: false,

};

onClick = () => {

this.setState({ clicked: true });

};

render() {

return (

<button onClick={this.onClick}>

{this.state.clicked ? 'clicked!' : 'click me'}

</button>

);

}

}Not too exciting, but it does the job well enough. Let's take a closer look at the onClick handler:

onClick = () => {

this.setState({ clicked: true });

};setState Accepts A Reducer

Take a close look at the argument to this.setState. What if I told you setState always used a

reducer to update this.state? How could that be? It's just an object, right? As it's written,

it's tough to see how an object could be a reducer, so let's take a peek under the hood and see

what's actually going on when you call this.setState with an object parameter.

It probably looks something like this, right?

// NOTE: this is not the real React source

class Component {

state = {};

setState = newState => {

this.state = newState;

};

}Not quite. If we look at the docs for

setState, we see that it accepts either an object or a function as the first parameter. If you

pass a function it should have the following shape:

Your state updater function should accept a copy of the current component state and return a new

object that represents the new state after your modifications have been performed. If you just pass

an object to setState instead of a function, React will automagically transform it into an

updater. Let's update our psuedo-implementation:

// NOTE: this is not the real React source

class Component {

state = {};

setState = updaterOrNewState => {

let updater = updaterOrNewState;

if (typeof updaterOrNewState === 'object') {

updater = () => updaterOrNewState;

}

this.state = updater(this.state);

};

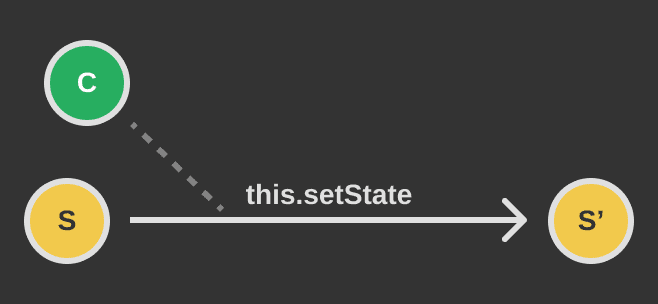

}This still doesn't look like a reducer though, right? It's just a straight line, a single input (the previous state) and a single output (the updated state). Where's the Y-shaped, 2 becomes 1 pattern? Let's pull off this ninja reducer's mask!

The Big Reveal

The missing piece of the puzzle here, the second input to the setState reducer, is the

closure! JS implements function closures, which means any operation has access to any and all

variables that were in scope when it was declared. An operation's scope includes the function that

closes around it, as well as any higher level functions that close around that function, all the

way up to the global scope. This is sometimes also referred to as a function's context.

So, even though this.setState's updater only accepts one input paramater, it accepts a second

source of input in the form of the surrounding context. Sometimes we don't care about the context

and just throw it away, like:

this.setState(prevState => ({

clicked: true,

}));The important takeaway is that the context is always available, even when we don't use it. Many things can be part of context, from function parameters to class instance variables all the way up to global dependencies, as shown below.

import { data } from '../data';

const MINIMUM_VALUE = 0;

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

/*...*/

onClick = (foo, bar) => {

this.setState(prevState => ({

foo,

bar,

baz: this.props.baz,

qox: 'qox',

quuz: MINIMUM_VALUE,

fizz: prevState.count + 1,

buzz: data,

}));

};

/*...*/

}We can still find our Y-shaped, 2 becomes 1 pattern, we just have to look a little closer! Reducers are everywhere, you just have to know how to look for them.